You remember when you used to wait what seemed like a day to transfer one song to your iPod in the early 2000s? Those first iPods had an added feature of a FireWire cable that was capable of hurling data far beyond USB capability. However, nowadays, FireWire ports are the exception, as floppy disk drives are. What became of this technically superior interface, and why did the inferior USB end up winning?

The answer shows a very simple truth about technology: the best does not necessarily win.

The Tale of Two Interfaces

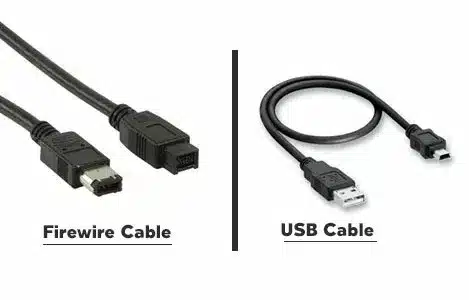

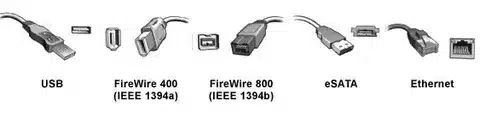

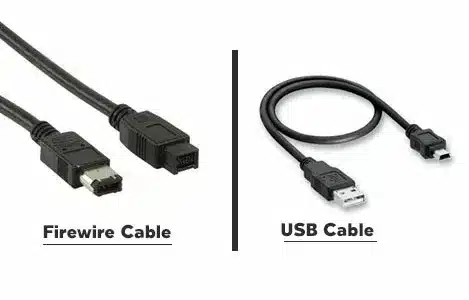

Of course, we need to know what we are dealing with before we sink into this David vs. Goliath story.

USB (Universal Serial Bus) turned out to be the ubiquitous connector- a flexible, cheap connector that was meant to eliminate the mishmash of parallel ports, serial ports, and proprietary connectors in our computers. You can call it the Swiss Army knife of connectivity.

FireWire (IEEE 1394) was designed to perform rather than to look good; originally designed with audio and video work with high demands in mind. It was promoted by Apple, adopted by Sony, and vowed on by professional content producers.

Under the Hood: Where FireWire Flexed Its Muscles

Architecture That Made Sense

Whereas USB was more of a traditional office setup (whereby everything had to pass through the boss (your host controller on your computer) FireWire was more of a workspace. Its peer-to-peer design also implied that the devices were able to communicate with each other without the involvement of a computer.

It was only in imagination that two FireWire hard drives would be connected and your data would automatically be synchronized between them even as you worked on a different task altogether. USB devices? They had to use the computer to act as an intermediary for every transaction.

Speed That Actually Delivered

The raw numbers are also included in the story: FireWire 400 has hit 400 Mbps, and USB 2.0 has hit 480 Mbps. It gets interesting here, though-Full-duplex implementation of FireWire, it was possible to send data in both directions simultaneously as opposed to USB, which is one direction at a time, like a two-lane highway or a one-lane tunnel.

This was not a nice-to-have feature for the video editors who had hours of video to edit, and getting coffee was better than getting lunch.

Power to Spare

FireWire was not just carrying information; it was actually effective. USB 2.0 was gingerly delivering 2.5 watts when FireWire was promising 10-20 watts, and could potentially deliver 60 watts. External hard drives booted immediately, cameras charged during the hours-long transfers, and professional audio interfaces automatically booted without wall adapters.

The Daisy-Chain Dream

FireWire was graceful in its topology: a maximum of 63 devices could be linked in a daisy-chain. No confusion with hubs, no nightmares about devices that are not recognized. Two or more interfaces, storage drives, and control surfaces could be connected in one continuous workflow.

The Plot Twist: Why Better Tech Lost

The Economics of Adoption

This is where the plot has a well-worn twist. The biggest strength of USB was financial rather than technical. FireWire had high costs in terms of costs of special controllers and licensing, whereas USB had very low costs. The mathematics was easy when manufacturers needed to decide between a $2 USB and a 10-dollar FireWire.

The Compatibility Trap

USB was compatible with all. It was backward and forward-thinking, and it was manufacturer-agnostic. FireWire stayed mostly within the ecosystem and professional niche of Apple, though technically superior. Once consumers were forced to decide between a system that was compatible with all or a system that was perfect with a few things, they picked universality.

The iPhone Moment

And the last nail in the FireWire coffin was not pounded into place by a competitor–it was pounded in by its largest proponent. The message became apparent when Apple discontinued FireWire as a consumer product in favor of USB and developed Thunderbolt as a professional use case: FireWire was dead.

Why This Ancient Battle Still Matters

Lessons in Standards Wars

The history of FireWire teaches us that better technology is not enough. The ideal combination of performance, price, compatibility, and ecosystem support is needed to achieve market success. It is a lesson that we have learned several times with Betamax vs. VHS, HD-DVD vs. Blu-ray, and dozens of other format wars.

Legacy Lives On

Amazingly, FireWire is not totally dead. FireWire interfaces are still used in professional audio studios because of their rock-solid streaming performance. VCRs with FireWire are still the preferred option for transferring old family videos. Most of the modern advances made by USB, such as the power delivery and peer-to-peer features of USB-C, will have their analogs in FireWire innovations of twenty years ago.

Modern Echoes

The modern Thunderbolt is the combination of the performance philosophy of FireWire and the practical approach of USB. USB4 finally provides the bi-directional speed introduced by FireWire. Even the power delivery features of USB-C are based on what FireWire had demonstrated was possible several years ago.

When FireWire Still Makes Sense

Legacy Equipment Integration

FireWire can also be a more reliable and smoother transfer when working with older DV cameras, vintage audio interfaces, or older storage systems than USB adapters. Real-time applications remain a shining star of the streaming-optimized protocol.

Professional Audio Workflows

A large number of professional audio engineers remain loyal to FireWire interfaces due to their predictable latency and streaming. USB just does not work with the variable performance required when you are recording a live orchestra.

Choosing the Right Adapter

Thunderbolt-to-FireWire adapters allow modern systems to access FireWire devices without sacrificing the benefits of the protocol, but providing an entry point into modern computers.

The Future of Connectivity Standards

With USB4 and Thunderbolt 4 duking it out in the streets, the ghost of FireWire cries out: Are we finally getting interfaces that are easy to use and offer the no-quarter performance? Or is it destined that we repeat the same process wherein good enough defeats genuinely great?

The question may be whether we’ve learned the lesson of FireWire–that the most successful product in technology is not necessarily the best, but the most available.

Comparison at a Glance

| Feature | FireWire (IEEE 1394) | USB (2.0 to USB-C) |

| Architecture | Peer-to-peer, daisy-chain | Host-controlled, tiered-star |

| Speed Range | 400-800 Mbps | 480 Mbps → 40+ Gbps |

| Data Flow | Full-duplex | Half-duplex → Full-duplex |

| Power Delivery | 10-20W (up to 60W) | 2.5W → 240W |

| Device Capacity | 63 devices (daisy-chain) | 127 devices via hubs |

| Primary Use | Audio/video, professional | Universal connectivity |

| Cost Factor | Higher implementation cost | Low cost, mass adoption |

| Current Status | Legacy/niche applications | Dominant standard, evolving |